The Durham Sanctuary Knocker

The Sanctuary Knocker, a lion bold, A warning of fate, to those who are told, Of the Hellmouth, a gateway to sin, A reminder of fate, to those who enter in!

The Sanctuary Knocker at Durham Cathedral is a remarkable and ‘striking’ piece of medieval history. Commissioned by the cathedral’s monks in the 12th century, the knocker was installed on the North Door and is a sizable hunk of bronze. Its design features a lion, crowned by its flowing mane, capturing a man who is being consumed by snakes.

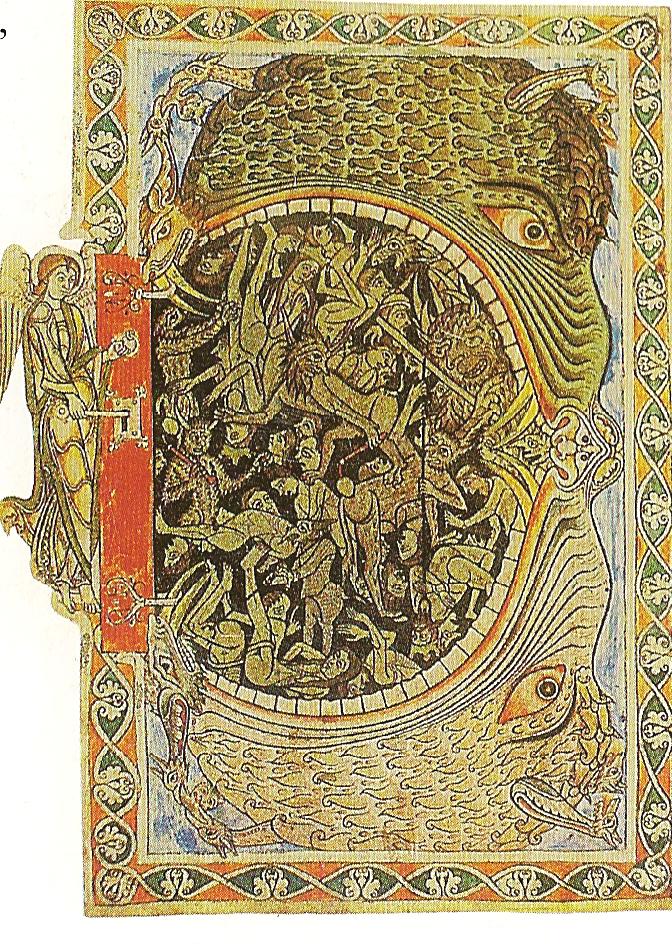

This design is based on the ‘Hellmouth’, a medieval image depicting a literal entrance to hell through the gaping jaws of a beast.

The Sanctuary knocker was used by individuals seeking refuge in the Cathedral, often criminals fleeing from the law. Sanctuary was a legal right in medieval England, where people could claim protection from the church, and they would be safe from arrest within the church’s grounds. The Sanctuary knocker was a symbol of this protection, and it was used to signal to the monks that someone was seeking refuge.

An interesting aside is that of Robert the Bruce who sought sanctuary in Durham Cathedral in 1306 after he had committed murder in a confrontation with a rival noble, John Comyn. The conflict arose as Bruce was aspiring to become king of Scotland and Comyn, a powerful figure, opposed his claim. In a fit of rage, Bruce killed Comyn in the church of Greyfriars in Dumfries, which was a significant act of violence that galvanized opposition against him.

After this event, Bruce fled and sought refuge in Durham, which was a stronghold of English power. The cathedral was known for offering sanctuary to those in peril, allowing them to seek protection from their pursuers. Bruce’s presence in Durham was also a strategic move, as he aimed to regroup and solidify support for his cause amidst the tumultuous political landscape of the time. Eventually, he would go on to become a key figure in the Scottish Wars of Independence, culminating in his victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

The Hole in the heed

The legend tells of a man being pursued by the 'authorities' who is seeking sanctuary. An arrow narrowly missing his head, instead embedding itself in the sanctuary knocker just as he sought protection!

A Potted History of Hellmouths!

It was crafted from bronze and took the form of a lion haloed by its mane, devouring a man whose legs are being eaten by snakes.~ Unknown Monk

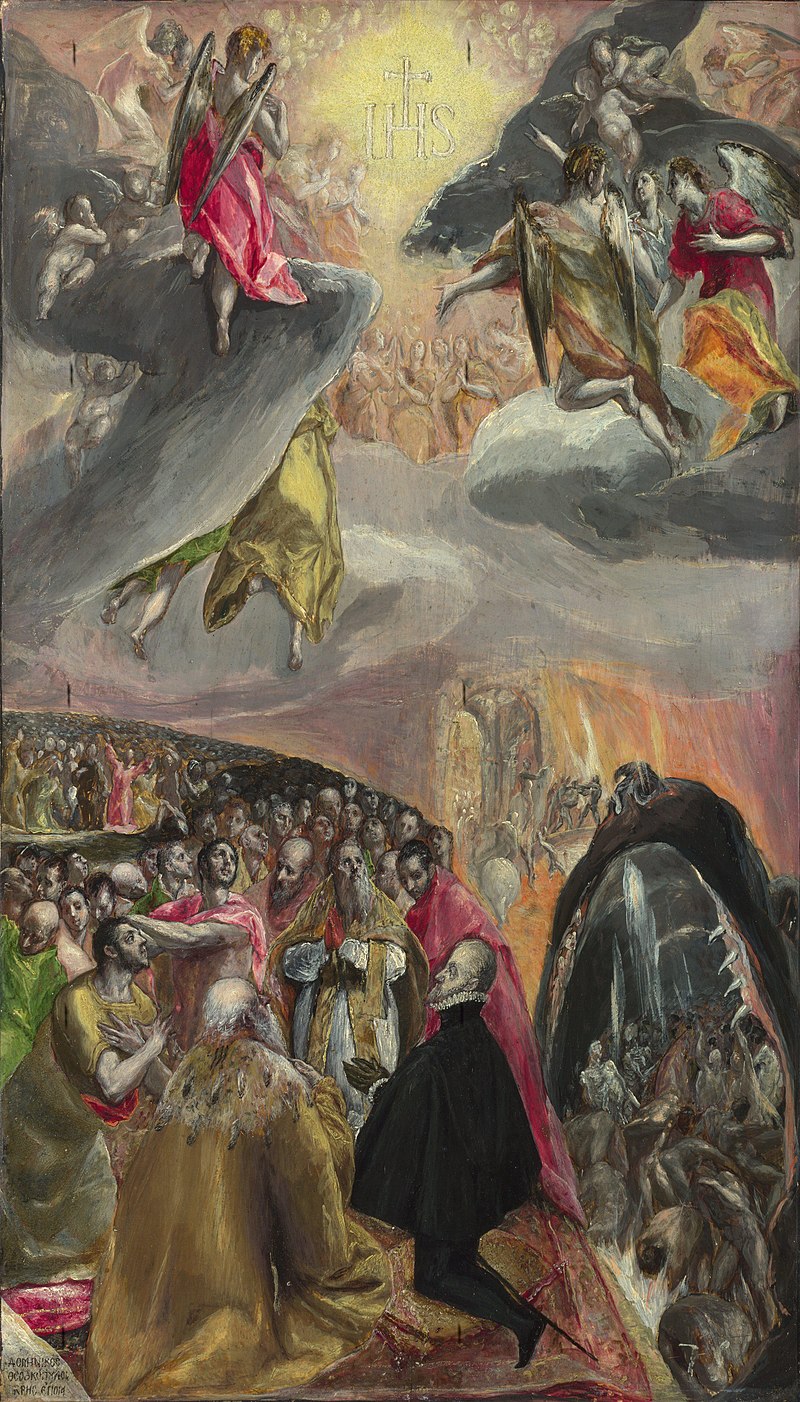

The concept of the “Hellmouth” is a medieval image depicting a literal entrance to hell through the gaping gob of a demonic beast. This image was often used as a warning and deterrent of sin, and can be found in various forms in medieval art and architecture. They were often depicted in churches as a reminder of the consequences of one’s actions and the importance of seeking redemption. Notable examples of Hellmouths can be found in the illuminated manuscripts of the 8th century and the sculpture of the Romanesque period, specifically in the 11th century.

In folklore, the Hellmouth is often associated with the idea of a gateway to the underworld or a portal to the realm of the dead. It was believed that the mouth of the beast would open during times of great sin or moral decay and swallow up the souls of the damned. Imagine the portal size required today…but I digress! Some stories tell of brave warriors or holy men who ventured into the Hellmouth to rescue the souls of the damned or to defeat the demons that guarded the entrance. These tales can be found in various written accounts of the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Sanctuary knocker at Durham Cathedral, commissioned in the 12th century, is one of the most well-known examples of a Hellmouth in architecture. It serves as a reminder of the legal right of sanctuary, the moral and spiritual implications of seeking refuge, and the skill and artistry of medieval craftsmanship. The Sanctuary knocker serves as a unique and striking reminder of the medieval perspective on sin, redemption, and the afterlife.

In 1297 Durham, The typical monks day.

A Typical Day for a Monk in Durham, 1297

The daily life of a monk in 13th-century Durham followed the strict rhythm of the Divine Office (the eight canonical hours of prayer) combined with work, meals, and rest. Here’s how a normal day unfolded:

Before dawn (~2–3 AM)

The bell rings for Matins, the first and longest service of the night, followed immediately by Lauds.

~6 AM – Prime

The monks return to the church for the short dawn prayer of Prime, marking the official start of the day.

Morning (~6:30 AM – 11 AM)

Manual labour or assigned duties:

- Tending gardens or farm work

- Copying manuscripts in the scriptorium

- Cooking, cleaning, or other tasks for the community

~9 AM (brief interruption)

Terce – a short mid-morning service.

~11 AM – Noon

Chapter Mass (or the main conventual Mass) followed by the main meal of the day in the refectory.

Typical menu: bread, pottage (vegetable stew), beans or peas, perhaps fish (on non-meat days) or cheese, and ale or water. Meat was rare except for the sick.

Early afternoon (~Noon – 2 PM)

A period of rest, reading in the cloister, or private study.

~2 PM – Sext

Midday prayer service.

Afternoon (~2:30 PM – 6 PM)

A lighter second meal (often just bread, vegetables, and ale), followed by more work until late afternoon.

~6 PM (or just before sunset) – None

The fifth service of the day.

Evening (~6 PM – 9 PM)

Time for reading, study, or limited recreation (conversation, walking in the cloister, occasionally chess or other permitted games).

~8–9 PM – Compline

The final night prayer. After Compline, strict silence began (“the Great Silence”).

~9 PM

The monks went to bed in the dormitory, sleeping in their habits on simple straw mattresses, ready to rise again when the bell rang for Matins a few hours later.

This cycle of “ora et labora” (prayer and work) repeated every day with only minor seasonal adjustments for daylight. Even on feast days, the structure stayed largely the same, though work might be reduced and the meals improved.

The Typical Life.

In 1297 Durham, monks lived in monasteries that were often located in remote, pristine environments. These locations were intentionally chosen to provide a peaceful and serene setting for religious contemplation and worship. Monks would spend their days in prayer, study, and manual labor, such as working in the fields or tending to the monastery gardens. The natural surroundings offered a clean and healthy environment, free from the pollution and disease more prevalent in densely populated urban areas.

If you enjoyed this please consider subscribing or sharing, many thanks.

There is also a store with some article related merchandise for you to plunder at will with a 10% discount. Please quote #peasantstore

It all helps, cheers. X